100 years after it ended - How it began for one soldier

My great uncle Basil was the old guy my parents dragged me out to visit every so often. His house smelled of things past their prime; heavy furniture that shone with a century of beeswax polish, drapes that had closed on three generations, footstools hand embroidered to celebrate Queen Victoria’s reign. He lived with his slightly younger spinster sister. I thought that was weird. Sometimes he’d come to our house (along with a bunch of other old relatives) and I’d have to sit through dinners or lunches with them. I knew that Uncle Basil had been a bank manager. It sounded like a boring job to me, except for when I learned that his branch had been robbed and he fought off the robbers – I thought that was cool. He had a mischievous sense of humour and an infectious laugh that made me giggle.

He died when I was 21, a time when I thought I was living a much more interesting and exciting life than he ever had. It wasn’t until I was in my 40’s, when I was cleaning out my parents’ house and found his letters home from WWI, that I discovered what a truly amazing life he’d lived.

Lance Corporal Basil B. Vale

He was in his early 20’s when he wrote those letters and by the time he was discharged from the Canadian Expeditionary Force he’d already lived a much more interesting and brave life than I still have yet to live. I wish I’d appreciated him more when he was here. I wish I’d known his older brother, my great uncle George.

George and Basil willingly risked their lives to defend their King and country in The Great War. They didn’t talk about history – they lived it.

George was 21 when he signed up in January 1916. He left Canada on the RMS Olympic (the Titantic’s sister ship) on April 28, 1916, sailing from Halifax to Liverpool. He served with the Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion.

RMS Olympic

Basil was 20 when he signed up on September 28, 1917. He sailed from Halifax on December 21, 1917 on the RMS Grampian. He served with the 2nd Battalion Canadian Engineers.

RMS Grampian

George was discharged in July 1919. Basil was discharged in April 1919.

Canadian soldiers returning home to Toronto.

Next Sunday will mark 100 years since the Armistice was signed, the day when we remember all of our armed forces and the sacrifices they have made and continue to make.

Below is Uncle Basil’s first letter home from England, written as his war experience was just about to start. Little did he know what lay ahead of him on the battlefields in France.

(NOTE: Basil accidentally wrote the year 1917 instead of 1918, probably because he wasn’t used to writing the new year. Military records show that he sailed into Halifax harbour barely two weeks after the Halifax Explosion of December 6, 1917.)

Seaford Camp, Sussex

January 2nd 1917

Dear Ma:-

How are you anyway and what sort of Christmas did you have? It was a big event I bet and all had a dandy time.

We only landed here yesterday and had a wonderful voyage or rather I had and I was not seasick all the way over although for three days there was a big storm on but some of the poor fellows found it pretty hard to eat anything.

The Grampian was the name of the boat and she is a good sailor too. There were eight boats to the convoy and the only one I could get the name of was the Missanabie but to start from the beginning. On December the 15th we were called at three thirty a.m. and between that and ten o'clock we handed in our blankets except two and had breakfast and handed in the rest of the kit we did not need. It was at this time that sister Bernadette's picture came and as you know I had not a place I could carry it without folding and this would spoil it which would be a shame as it was a beautiful calendar.

We were marched down to the train and on the way we were inspected by the Duke and his staff. After we got on the train there were thousands of people to see us off. It was at this time that the Chapins found me and gave me that big box with biscuits, a cake, three oranges, three apples and a load of candies. You do not know how glad I was to get this. I had saved the jam out of my other box and that certainly tasted good when I did eat it but I will tell you about that later. So with the thermometer down at 38° below we pulled out of Ottawa at eleven o'clock. It was at Montreal that I posted the first letter and I posted the rest on the way and when we landed at St. John I gave a kid a nickle to post one for me so it would get through. We did not get to St. John until Tuesday morning. All the way along the train was stopped in the middle of the country for maybe five or six hours and at one time the officers’ car was frozen up and we waited for nearly all day Sunday until they got a new one for them. We had a dandy comfortable car and only two fellows to a seat. This meant we each had a birth but the other fellow I was with and myself slept in the bottom bunk and packed all our equipment in the other. You know they turn the heat off in the sleepers at night time and the two of us had eight blankets and could not have been warmer. All the meals in the train were served to us by the G.T.Ry. [Grand Trunk Railway] and sure were good.

All the way along we passed troop train after troop train or more passed us rather than we passed them. So at ten o’clock on Tuesday morning we arrived or rather got off the train in St. John. The train stopped right at the docks and we marched right on the Grampian. It was on this night that I went on guard for the night only. The boat was docked all night and did not pull out until three o'clock on Wednesday afternoon. The Missanabie which was in the opposite dock to us pulled out right after us. We sailed until the next morning at eleven when we pulled into Halifax harbour. The sea was quite calm all the way but the sight of Halifax was terrible. All the trees have not a branch on them and all the houses are either right on the ground or where there were brick ones and brick factories one or two walls stand. We saw the munitions ship and the Belgium relief ship and two or three others partly blown to pieces. We saw one box car that was blown clear across the harbour. All this we saw from the boat. When we got in the harbour there must have been six or seven other ships waiting there too.

RMS Missanabie (Torpedoed by U-boat U-87 and sunk September 9, 1918.)

Among them was the Calgarian a converted cruiser which escorted us over and another boat was loaded with Americans. Well we stayed in Halifax all night and pulled out Friday at three p.m. with all the other boats all in the line.

HMS Calgarian (Torpedoed by U-boat U-19 and sunk March 1, 1918.)

Our boat was one of the flagships in the bunch and was the fastest boat so all the way over we kept circling back around the others and keeping our eye on them.

There was a forestry battalion from Toronto on board and a battery from St. John's NF and two batteries from Toronto.

In one of these batteries was a fellow from the bank by the name of Marshall. There were only three nurses on board our boat and as none of them looked me over I guess that Greta's friend must have been on the Missanabie with a large number of other nurses on board there. I could not very well look her up as they travelled first class with the officers and four or five passengers and not knowing her name made it worse too or I might have got one of our officers to find out.

The forestry battalion was the funniest lot of fellows I ever ran up against. Four out of every five of them were real nuts, simple minded as could be and the remainder were rough was no name for it. I mean by rough uncultured.

Do you remember at 713 Ontario the man you had to clean carpets and when you gave him fried eggs for brunch and he cut them in half and with four turns of the knife bingo the eggs were gone well that describes the forestry bunch to a T.

I was on the second sitting you know. That means the second serving. I could not have struck better luck on this as the first sitting's breakfast was at seven and the second at eight so this let me have an extra hours sleep.

On Sunday the boat began to rock and it was then that nearly all the fellows had six meals a day. Three down and three up. This storm or rather it was hardly a storm until Christmas Eve when it sure was a storm. All the way over I was not a bit sick. This was good and bad luck at the same time. So many of the fellows were sick I struck guard three times but now we land at Christmas and one I never hope to spend the like of again not that they did not put up a ripping good meal with chicken, roast potatoes, green peas, a mince pie to each man, Christmas pudding and an orange and an apple to each man but I was so darn homesick I did not enjoy it but I took the mince pie and apple and orange to my bunk and ate them the next day and they sure did go good then.

All the way over we had to wear our life belts and at ten o'clock each morning the roll was called and then we were dismissed for the day except for those who wanted beer and they paraded at three fifteen. Twice they had free beer and I was in the lineup. They soaked the fellows twenty cents a bottle for it and it wasn't worth ten. There were four fellows to a room and on the twenty-fourth one fellow went to the hospital with tonsilitis? and on the twenty-fifth another went with trouble with his apendix so both stayed there until the thirty-first.

One fellow was given eleven boxes when he left Ottawa and these and what the rest of us had we had fifteen boxes all together and this lasted us pretty near all the way.

On the thirtieth we were met by eight destroyers that kept going all among and around the boats and it was as funny a thing as ever you saw at night to see them signalling by lamp. They looked like a bunch of fire flies all over. You know there is not a light on the ships and everything was pitch dark. These lamps you know are strong lights that flash dots and dashes.

On December the thirtieth we sighted the North coast of Ireland at twelve noon. It was on the morning of December the thirty-first we woke up and found ourself in Greenock, Scotland. There was a pilot boat sent out to meet us and was torpedoed so we had to hike to the first port. At ten o'clock we sailed up the Clyde to Glasgow and a prettier sight I have yet to see. The scenery was gorgeous and we were quite a novelty to the people on account of the boat being the first troop ship to come this way. We were pulled up the river by tugs and got to the outskirts of Glasgow at one o'clock and kept going right on for two and a half hours. I never saw so many boats being built. If there was one there were a thousand in all stages of construction both big and small. All the way down the Clyde the people ran down to the river and cheered. The boat docked at three forty-five. I would have liked to have nurse Brown's address and I think I could have had one of the dock hands look her up and she could come down to the boat. We were kept on the boat until six-thirty and one of those cockney compartment trains was pulled up on the wharf and we were put right on it. Nobody was allowed on the wharf so we did not see much of the people of the town. Again I was in luck on account of my name beginning with a V. I am in No.8 platoon of B Company which is the very end. You may be sure they would not be short of cars so by the time we got on instead of being six to our compartment there were only three.

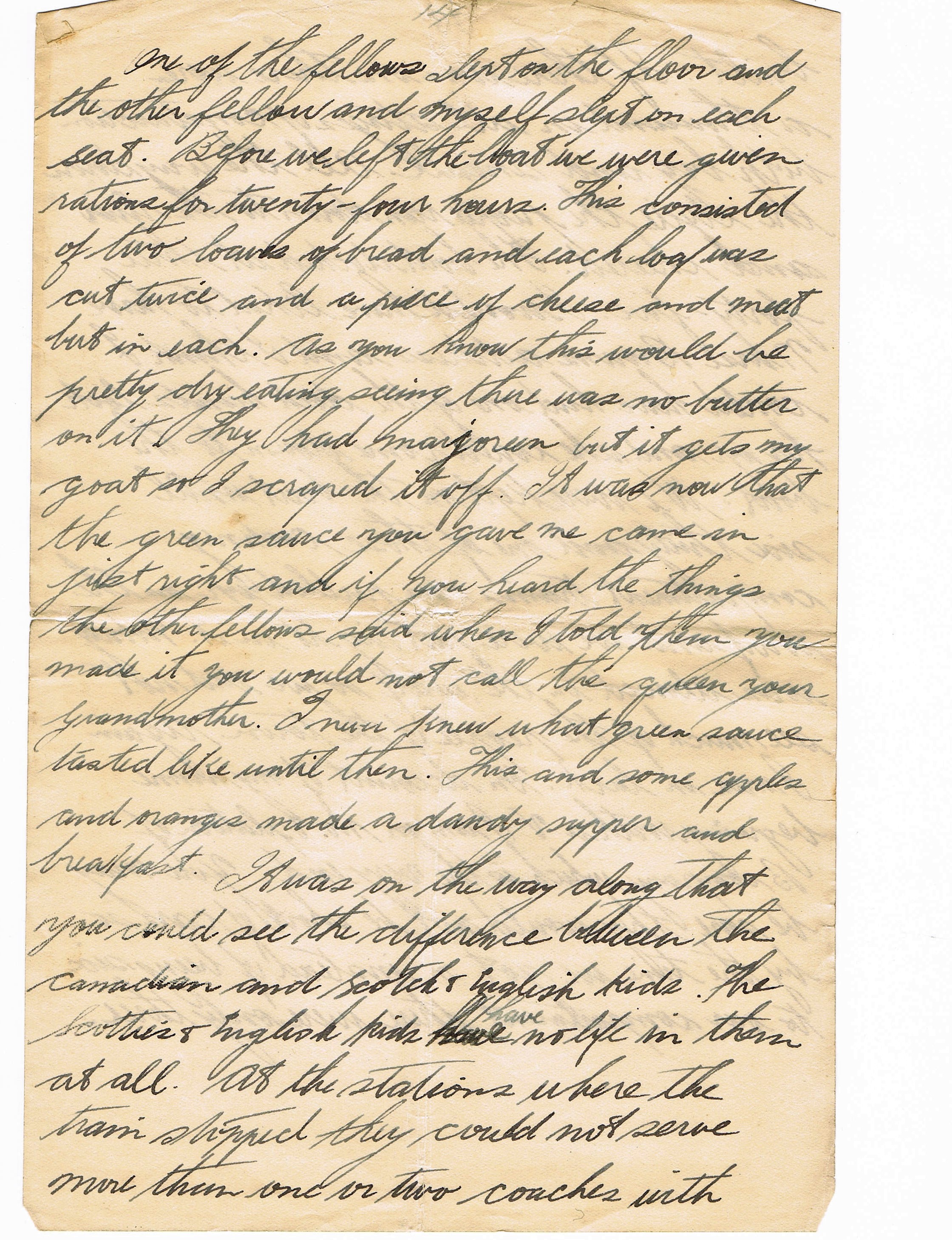

One of the fellows slept on the floor and the other fellow and myself slept on each seat. Before we left the boat we were given rations for twenty- four hours. This consisted of two loaves of bread and each loaf was cut twice and a piece of cheese and meat put in each. As you know this would be pretty dry eating seeing as there was no butter on it. They had margarine but it gets my goat so I scraped it off. It was now that the green sauce you gave me came in just right and if you heard the things the other fellows said when I told them you made it you would not call the queen your Grandmother. I never knew what green sauce tasted like until then. This and some apples and oranges made a dandy supper and breakfast.

It was on the way along that you could see the difference between the Canadian and Scotch and English kids. The Scotties and English kids have no life in them at all. The stations where the train stopped they could not serve more than one or two coaches with papers and candies where our kids could serve half a dozen trains. There were thousands of girls serving as baggagemen etc. and nearly every woman over here carries a man's walking cane.

We slept pretty nearly all night and arrived at Seaford Thursday morning at a quarter to eleven and believe me the English know how to run a troop train. I was never on a train that went so fast and there was no side tracking like at home. The train had the right of way all the time.

When we got off it did not take us long to know we were under English military rule for sure for instead of carrying our kit bags in a motor truck for us we had to carry them both with our haversack, water bottle and bandoliers and blankets in bandolier fashion. I should say the outfit weighed at least a hundred pounds and with our great coats on to carry this was no sinch however I should not criticize them for they had their band and a fine turn out to meet us. All our fellows that left about a month before us to reinforce the Princess Pats are here too.

We are all in quarantine for ten days and yesterday we were inoculated and had a medical exam. This marks the second medical exam for us since we landed. The huts hold thirty-two men each and the mud is about that many inches deep but the inspection they give you for dress each morning is not nearly as strict as Ottawa. The meals it would be impossible for them to be better and are cooked in regular English fashion with lots of greens. This is what you would call spinach cabbage etc. isn't it?

Well Ma I have tried my best to let you know all about the trip but on a bunk only four inches from the ground and in candle light it is very hard to write but hoping you may be able to make something out of it and that you and Father and little Betty as well as the rest of the family are all in the best of health I will close this letter.

Your loving son

Tub